on

12-minute read

Writing Highly Maintainable WCF Services

When it comes to writing maintainable software, there is no alternative to the five core principles of object-oriented design. When software is based on these principles, everything becomes significantly easier. When your software is based on these principles, writing a highly maintainable WCF web service on top of that can be done in just a matter of minutes.

Most of my clients have maintainability issues with their software. Almost always these problems are caused by improper software design. Incorrect design can have many causes, such as bad requirement analysis, and high pressure. Bad design can even cause more bad design and even bigger maintainability nightmares. When looking closely at such design, I often see a violation of the five basic design principles of object oriented design; the SOLID principles. For me, there is no alternative: writing maintainable software starts with the SOLID principles.

Just as bad design triggers more bad design, good design can trigger more good design. For instance, after correctly applying the SOLID principles to your software, it will be much easier to write (web) services that are highly maintainable. In my last few articles (here and here) I described a way of modeling important parts of a software system in such a way that it increases maintainability (by simply following the SOLID principles). By modeling both business operations (commands) and business queries as messages, and hiding the behavior for processing these messages behind proper abstractions, the maintainability and flexibility increases dramatically.

Those command and query messages are simple data objects, which means that serializing them is easy. Being able to serialize those messages has a few clear advantages. You could for instance serialize them to a log file, which gives you a complete overview of what happened at what time and by whom. It’s a functional transaction log. Since both a command and a query contain all the data that is needed to correctly execute the operation (except perhaps some contextual information such as the current user), you could replay this information during a stress test or use it to debug a problem. By serializing commands to a (transactional) queue (such as MSMQ), you can even let commands run in parallel on background services. This can improve reliability and scalability of a system.

Another advantage of being able to serialize those messages is to be able to send them over the wire to a web service. Those messages can be used as the data contract of the web service, and the web service can be built as a thin layer that lies on top of that. With the right constructs and configuration, you can build this web service in such a way that it hardly ever needs to be changed. In this article I will show you how to do this with a WCF service based on the patterns described in my previous articles (so please read them if you haven’t).

WCF has a few interesting features, which make it an extremely convenient layer on top of a model based on commands and queries. For instance, WCF allows a service class to dynamically specify which types of messages the service can handle using the ServiceKnownTypeAttribute. This allows you to write the service once and never change it again. Another feature is the possibility to let the client and service share the same assembly. Of course this is only possible when the client is a .NET application as well, but this saves you from having lots of generated code on the client. This works best when the client and web service are part of the same Visual Studio solution, but you can also decide to share the contract assembly with third parties, for instance through NuGet.

This next code snippet is all it takes to make a web service that can handle any arbitrary command that’s available in your application:

[ServiceKnownType(nameof(GetKnownTypes))]

public class CommandService

{

[OperationContract]

public void Execute(dynamic command)

{

Type commandHandlerType = typeof(ICommandHandler<>)

.MakeGenericType(command.GetType());

dynamic commandHandler = Bootstrapper.GetInstance(commandHandlerType);

commandHandler.Handle(command);

}

public static IEnumerable<Type> GetKnownTypes(

ICustomAttributeProvider provider)

{

var commandAssembly = typeof(Contract.OneOfMyCommands).Assembly;

var commandTypes =

from type in commandAssembly.GetExportedTypes()

where type.Name.EndsWith("Command")

select type;

return commandTypes.ToArray();

}

}

This service has just one operation, decorated with the OperationContractAttribute. It can process any command. Since WCF needs to know what messages it must accept (to be able to generate a WSDL for instance), the service is decorated with the ServiceKnownTypeAttribute. This attribute points at the public GetKnownTypes method, which is part of the service. This method simply queries the metadata of the assembly containing all commands. This method uses convention over configuration—it expects all types in that assembly which name ends with “Command” to be command messages. However, other ways to retrieve the applicable command types (such as defining them by a common ICommand interface or marking commands with attributes) will do just fine.

The service’s Execute method accepts any possible command, and it uses reflection to build the corresponding ICommandHandler<TCommand> interface for the supplied command. It requests this handler from the Composition Root and uses a bit of reflection again to execute that command. The performance impact of the reflection is negligible, because the WCF pipeline (with all its deserialization and verification) obviously has much more overhead (but if needed, performance can be improved by caching the types).

The Composition Root is the part of the application where services are tied together and object graphs are composed. Here is how this Composition Root might look like:

using System.Linq;

using System.Reflection;

using System.Web.Compilation;

using SimpleInjector;

using SimpleInjector.Extensions;

public static class Bootstrapper

{

private static Container container;

public static void Bootstrap()

{

container = new Container();

var assemblies = BuildManager.GetReferencedAssemblies()

.Cast<Assembly>();

container.Register(typeof(ICommandHandler<>), assemblies);

container.Register(typeof(IQueryHandler<,>), assemblies);

container.Verify();

}

public static object GetInstance(Type serviceType)

{

return container.GetInstance(serviceType);

}

}

Not surprisingly, I use the Simple Injector to bootstrap the application; Simple Injector makes batch registering generic types and generic decorators embarrassingly easy. However, any descent DI container will allow you to do this in one way or another. The first call to the Register method iterates through all application assemblies and registers all concrete ICommandHandler<TCommand> implementations that it finds. This of course is just a simple example.

The Bootstrap method is called during application startup. For a WCF service this will be the Application_Start event in the Global.asax:

public class Global : System.Web.HttpApplication

{

protected void Application_Start(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

Bootstrapper.Bootstrap();

}

}

With these three pieces in place we have a working WCF service that can accept command messages from a client. If you haven’t already, you can start defining commands just like the following:

public class MoveCustomerCommand

{

public int CustomerId { get; set; }

public Address NewAddress { get; set; }

}

Notice how this type lacks any WCF DataContractAttribute and DataMemberAttribute. When working with DTOs, WCF allows you to skip using these attributes, which simply means that WCF will serialize the complete instance, which is exactly what you want. Not only removes this noise from your code, it keeps your commands simple POCOs, free from any technology specific attributes, which is always a good thing.

I must admit that this whole design can seem a bit overwhelming, and not seem very appealing at first. But as I explained in my previous blog posts, this model starts to shine once you start applying Cross-Cutting Concerns to those handlers and can drastically lower maintenance when your application starts to grow. In my post about commands I made a small list of Cross-Cutting Concerns that are easy to implement as decorator, such as validation, audit trailing, and queuing. Besides these, when running a WCF service, it could be really useful to have a mechanism to prevent messages from being replayed (both preventing accidental duplicates and hacking). Adding such feature as a decorator would be pretty easy.

Commands are of course just one half of the story. Queries are the other half. Let’s cut to the chase; Here’s the service that can execute queries:

[ServiceKnownType(nameof(GetKnownTypes))]

public class QueryService

{

[OperationContract]

public object Execute(dynamic query)

{

Type queryType = query.GetType();

Type resultType = GetQueryResultType(queryType);

Type queryHandlerType = typeof(IQueryHandler<,>)

.MakeGenericType(queryType, resultType);

dynamic queryHandler = Bootstrapper.GetInstance(queryHandlerType);

return queryHandler.Handle(query);

}

public static IEnumerable<Type> GetKnownTypes(

ICustomAttributeProvider provider)

{

var contractAssembly = typeof(IQuery<>).Assembly;

var queryTypes = (

from type in contractAssembly.GetExportedTypes()

where TypeIsQueryType(type)

select type)

.ToList();

var resultTypes =

from queryType in queryTypes

select GetQueryResultType(queryType);

return queryTypes.Union(resultTypes).ToArray();

}

private static bool TypeIsQueryType(Type type) =>

GetQueryInterface(type) != null;

private static Type GetQueryResultType(Type queryType) =>

GetQueryInterface(queryType).GetGenericArguments()[0];

private static Type GetQueryInterface(Type type) => (

from interfaceType in type.GetInterfaces()

where interfaceType.IsGenericType

where typeof(IQuery<>).IsAssignableFrom(

interfaceType.GetGenericTypeDefinition())

select interfaceType)

.SingleOrDefault();

}

The structure of this QueryService is similar to what you’ve seen with the CommandService. However, because queries return a value, a bit more wiring must be done. When executing queries, however, there is one catch. Because the command service doesn’t return any data when processing commands, clients could easily let Visual Studio generate the service contract for them. Query objects, on the other hand, implement an interface that describes the data they return, for instance:

public class GetUnshippedOrdersForCurrentCustomerQuery : IQuery<OrderInfo[]>

{

public int PageIndex { get; set; }

public int PageSize { get; set; }

}

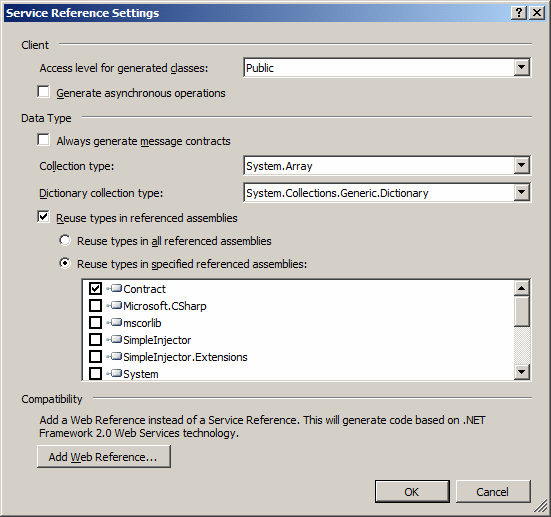

But WCF doesn’t communicate this interface through its WSDL definition and this part of the contract is lost. This problem can be solved by sharing the assembly that contains the query objects between the client and the service. Sharing an assembly between client and server is done by specifying it in the “Reuse types in specified referenced assemblies” option of the Advanced tab when adding the web service reference using Visual Studio’s “Add Service Reference” wizard:

Unfortunately, it is not always possible to reuse the same assembly. Especially when dealing with non-.NET clients. Those clients will either need to cast the returned object to the correct type manually or will have to write some infrastructural code that adds compile-time checking again (such as writing or generating partial classes to add this interface again to generated code). This of course only holds for clients written in statically typed languages. With a dynamic language, you’ll have a different set of problems :-).

This shared assembly functions as the service’s contract—not sharing that assembly will make you lose information about this contract. WCF doesn’t have the ability (at least not that I know) to express what data comes back from the service with what input—but not all is lost. This information is available in the metadata and documentation can be generated based on it. It could be as simple as shipping the XML documentation file that is generated by the C# compiler, or a Sandcastle documentation based on that XML file. This makes it easier for the client developers to work. Or the web service could even expose an extra method that returns a list with the names of all queries with their corresponding return type. This would make it pretty easy for the developers of the client to use this information to generate the proper code for their environment that adds type safety and compile-time support again (although this highly depends on the possibilities of the used system, runtime, and language).

In fact, this is all it takes to write a highly maintainable WCF service. Obviously your service should do the proper authentication, authorization, validation, logging, and all other sorts of Cross-Cutting Concerns. Authentication is typically done at the WCF layer, and almost all other Cross-Cutting Concerns can be implemented by registering decorators for ICommandHandler<TCommand> and IQueryHandler<TQuery, TResult>. This will keep the CommandService and QueryService clean from these sort of checks, and it will allow you to reuse this logic in other applications, running on the same business layer.

When you get the hang of this way of designing your system, you will appreciate how easy and flexible it is. Still, please take the following things into consideration:

- Don’t forget that although adding new commands and queries can be done without making changes to the

CommandServiceandQueryServiceclasses, the service’s contract will still change. Although adding new commands and queries would usually not be a problem, every change to an existing command or query object might break on of your clients. For example, changing validation logic of a command could break your client. Managing the contract and backwards compatibility with existing clients is especially crucial when the clients are external. That’s a problem that this model doesn’t solve. Of course, things are much easier when the client application is part of the same solution (and are deployed simultaniously), because contract changes can be made without a problem and you’ll even get compiler warnings on the client application when you make these changes. - Make sure the service contract only contains commands and queries that must be accessible from clients. If they’re not public, don’t place them in the contract assembly. If there’s no contract assembly, make sure

GetKnownTypesmethod does not return them. This should be as easy as changing the LINQ query inGetKnownTypes. Depending on the DI library you use, you might be able to leverage features of the DI Container to find out which registrations exist. Simple Injector, for instance, contains a GetCurrentRegistrations method, that returns a list of registered types. - Decorators are a great mechanism to extend behavior of command handlers and query handlers with Cross-Cutting Concerns like validation and authorization. This can be mixed with metadata (attributes) placed on the command and query objects to define what behavior they should have.

- Find a mechanism to communicate validation errors efficiently to the client. For instance, try a model where you can define validations in one place and let these validations be executed both on the server and client. You could for instance mark command properties with Data Annotations attributes to allow them to be executed on both the client as the server. You could extend this with custom server-side only validation.

- When your architecture is based on commands and queries, setting up a web service is really easy and almost maintenance free. This means that it can be very convenient to have multiple (almost identical) web services side by side, with slightly different configurations. Imagine a service for public clients with access to a sub set of commands and queries of a second service, meant for internal clients. This can be a nice extra layer of defense. Or both an (internal) WCF service and a public Web API.

- And of course apply WCF best practices when it comes to securing your web service (and do test this).

This is how I roll on the service side of my architecture.

Comments

Daniel Hilgarth - 04 July 13

You mention the ASP.NET WebAPI in the second to last bullet point. This usually is used to create REST APIs.

But a web service implemented with the approach you show here wouldn’t conform to the REST principles. Do you agree?

Steven - 10 July 13

Daniel, A design based on commands and command handlers is by nature use case driven compared to the resource-driven approach that the Richardson Maturity Model for RESTful services describes. Having a use case-driven web API is most suited when you (as a team) build both the web service and the client applications that make use of it. When exposing your web API to third parties however, you don’t really know what use cases their applications implement. So in general it is better for an externally exposed web API to be resource driven.

Implementing a resource-based API with commands and queries will probably be cumbersome. In that case you will probably have more success when implementing the web API on to of an IRepository<TEntity> abstraction instead of building it on top of an ICommandHandler<TCommand> abstraction.

Note that using a generic interface is still important, because this allows you to apply Cross-Cutting Concerns more easily, which will help you reach the goal that this blog post describes: having a highly maintainable web service.

Steven - 23 July 13

There’s an interesting video online from NDC Oslo 2013 about CQRS Hypermedia with WebAPI that goes deeper into the previous discussion about resource-driven and use case-driven architectures with Web API.

Alex - 03 March 15

I have a question: have you run into difficulties using an IEnumerable<T> as a query result type? I get a CommunicationException:

There was an error while trying to serialize parameter http://tempuri.org/:QueryResult. The InnerException message was ‘Type ‘System.Linq.EnumerableEx+<DoHelper>d__22`1My.Services.MyResult, My.Services.Contra..’ with data contract name ‘ArrayOfMyResult:http://schemas.datacontract.org/2004/07/My.Services.Contract’ is not expected. Consider using a DataContractResolver or add any types not known statically to the list of known types - for example, by using the KnownTypeAttribute attribute or by adding them to the list of known types passed to DataContractSerializer.'. Please see InnerException for more details.

I have triple-checked my type export code and IEnumerable<MyResult> is definitely exported. However, the underlying type is notIEnumerable, it is (in this example) EnumerableEx. This is an implementation detail that is controlled by the QueryHandler’s internal logic. Given that the QueryService returns a dynamic object, do you think that the DataContractSerializer is having trouble recognising the data contract type?

It’s definitely a difficulty in recognising the concrete type. I tried changing all of my IEnumerable<T> to List<T> (concrete list) and the problem was solved. Then I tried changing to IList<T> and the problem re-appeared. I believe it must be the way that WCF inspects the type of the outgoing object - it’s not smart enough to know what the exported query type should be. For now in my service I’ll just stick to using List<T>, but it would be good to know if anyone else has solved this in a better way.

Can you think of a way around this?

Steven - 04 March 15

Hi Alex,

I have been banging my head on this in the past a lot. My conclusion is that WCF serialization sucks and doesn’t really allow you to return right object graphs that are most practical for developers. Because of that, I moved away from WCF serialization altogether. Instead, my WCF contract now looks like this:

public void Execute(string name, string json)

Instead of relying on WCF to do the serialization, I use JSON.NET to serialize/deserialize objects from and to JSON (on both the client and the server). This works wonderfully well and has a few interesting advantages, but the serialization capabilities are most noticeable. JSON.NET can serialize/deserialize about anything. It serializes IEnumerable<T> and IList<T> without trouble. But just as cool, it can work with immutable types as well. These are things that standard .NET serialization simply can’t do.

Do note that this is not about changing from XML to JSON. I personally don’t care about the format the objects have on the wire. So the fact that I use JSON as a serialization format is accidental. I use JSON.NET because it is extremely flexible and can serialize all things. Switching from the default serializer in WCF to the DataContractJsonSerializer will not do the trick, because you are bound to the same limitations that WCF serialization mechanism gives you.

Matt - 30 September 15

Would love to see the body of your Execute(string name, string json) method…

Steven - 30 September 15

Hi @Matt,

Here is a simplified version of what I use in one of my projects:

[OperationContract]

[FaultContract(typeof(ValidationError))]

public void Execute(string typeName, string json)

{

try

{

Type commandType = typeof(ICommand).Assembly.GetType(typeName);

Type handlerType = typeof(ICommandHandler<>).MakeGenericType(commandType);

dynamic command = JsonConvert.DeserializeObject(json, commandType);

dynamic commandHandler = Bootstrapper.Container.GetInstance(handlerType);

commandHandler.Handle(command);

}

catch (ValidationException ex)

{

throw new FaultException<ValidationError>(

new ValidationError { ErrorMessage = ex.Message }, ex.Message);

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

Bootstrapper.LogExceptionToDatabase(ex);

Debug.WriteLine(ex.ToString());

throw;

}

}

Kaveh - 19 September 16

Hi Steven,

Why do you prefer to use a SOAP/WCF service when you’re not using some of its capabilities such as API metadata generation, client proxy generation and data serialization, why not a single MVC action with custom model binder? Can’t you leverage WCF extensibility to be able to build the service in the way you would like adhering to SOLID principles?

Steven - 19 September 16

Why do you prefer to use a SOAP/WCF service when you’re not using some of its capabilities such as API metadata generation

As a matter of fact, I don’t prefer SOAP/WCF at all. I think it’s overly complicated, configuration heavy, and its serialization possibilities are severely limiting. I actually prefer a Web API approach.

why not a single MVC action with custom model binder?

MVC with custom model binders is a lot of work. Instead, I use ASP.NET Web API with a custom delegating handler. Just take a look at the WebApiService project in the reference project. It’s a fully working example implementation of a Web API based on this approach. It even generates Swagger documentation for you.

Wish to comment?

Found a typo?

Buy my book

I coauthored the book Dependency Injection Principles, Practices, and Patterns. If you're interested to learn more about DI and software design in general, consider reading my book. Besides English, the book is available in Chinese, Italian, Polish, Russian, and Japanese.